Contents

Software Index

Devember '18 & Working with Big Projects

Flattened by a busy semester's workload, SEGFAULT devotes an entire month of her free time to working on a single software project: reverse engineering a raytracer made by the one and only Micha 'Scanlime' Scott. Is persistance the cure to burnout? Can SEGFAULT detangle the web of C++? Is graphics programming as fun as it looks‽ We will find out!

Written 2018-12-31 2291 words.

It's rare that I actually complete a project, but when I do i always feel underwhelmed by the amount of code produced compared to the amount of effort that went into creating it. This is pretty demoralising, and in recent times I have found myself lacking motivation. At the beginning of Decemeber this year I realised I hadn't actually finished a project in longer than I could remember. Between work, university and good old fashioned procrastination I hadn't made the time to get any FOSS work done.

Around the same time I through pure chance bumped into a thread on the Level1 Techs' Forum called "Devember 2018". Devember is a concept that has been run for a few years now. The idea is simple enough: you make a pact with your community to spend at least an hour a day working on a project you outline at the beginning of the month and stick with it for the 31 days of December. You have to blog publicly about your progress and publish your work as you go. Its billed as a way to encourage Young-bloods to learn to code, or pick up a new technology.

With well over a decade in front of an IDE behind me, too much of that spent on Linux, I most certainly am not a Young-blood; but all the same I saw Devember as an opportunity to get motivated about FOSS again. The Level 1 community sweetened the deal by offering a shiny gold forum badge to anyone who completes the whole month. For my month of community supported dedication to a single project I decided to finish something I started back in May; completing one of my old projects should give me a win, and get me motivated again.

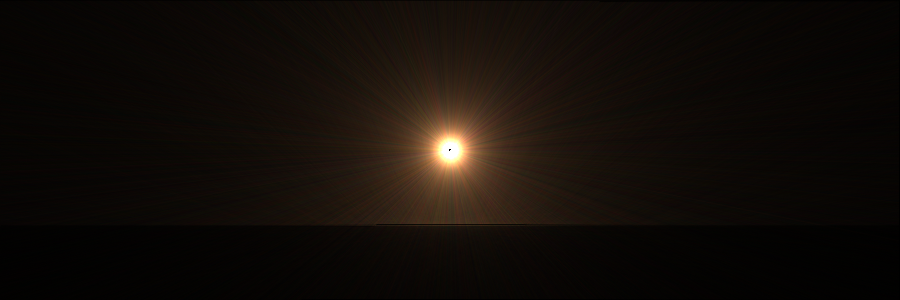

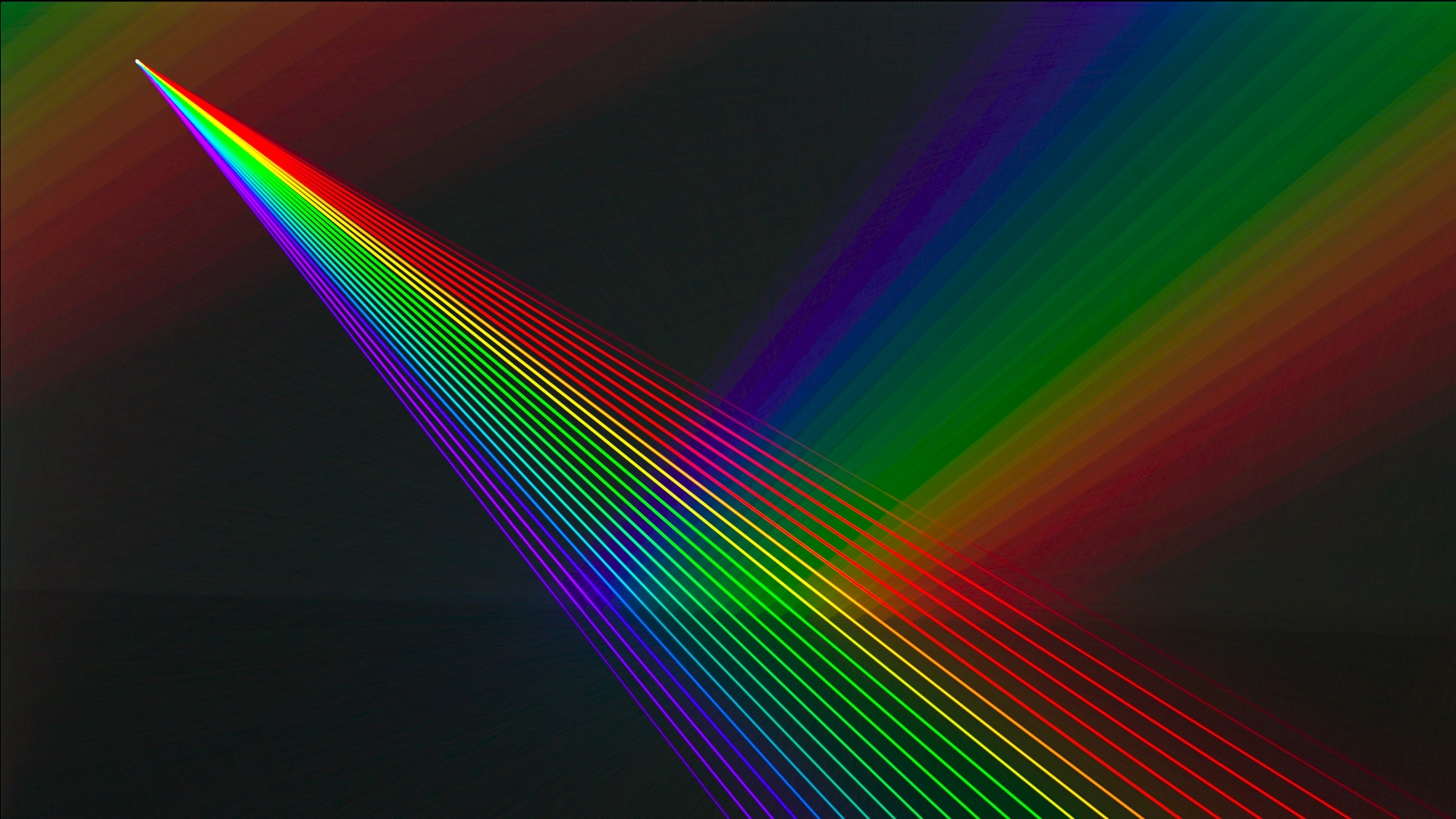

Zenphoton is a 2D ray tracing framework built by Micha Scott (@scanlime). It renders artworks defined from a scene file by simulating individual photons and tracing their path as they bounce through a 2D. space. I challenged myself to build a faster version of this project using Rust, which I dubbed Rustic-Zen. Rust has some great tooling making it easier to reason about your program which will be useful when trying to build something as complicated and high performance as a ray tracer.

I am pleased to report that the month of code has been a huge success, and my ray tracer is working (nearly) as it should. I sank significantly more than an hour a day into this work; you could argue that Devember worked a little too well, and some of my real work suffered for it. However I learnt a lot about what drives my FOSS work and how to best focus myself and get projects completed.

Blogging about your work:

As a requirement of Devember I had to keep a dev log of my work. Blogging about your work is a pain in the arse. It's extra time and effort on top of the time and effort you you put into your actual work. But while working on Rustic-Zen I have found it a great motivating force. Needing new content to write about every day to remain eligible for my forum badge meant that I needed to keep working on my code base. Even though some of my more frustrated posts in the dev thread were a single sentence, that requirement kept me bashing my head against the problem until I cracked it.

Another advantage to having a dev log is I have something to refer back to, which I actually used to write this blog post.

I didn't really have a methodology to writing my dev log though. I wrote as much as I had energy for at the end of the day's development, and usually just rambled about what I built, or the problem I solved. Some of my posts are actually single sentence rants on days where nothing worked and all I had to show for three hours work was a headache.

I think it works because you have to write something every day. It means you get to showboat when you achieve a day's work you're proud of and you get to rant and vent on days where the computer is your nemesis. I found it didn't really matter if anyone read it or not, shouting into the ether is therapeutic.

Reverse Engineering Big and Unwieldy Things:

The first half of this project was reverse engineering how the original version on Zenphoton worked. I picked up a couple of tricks for reverse engineering large chunks of software.

I have found a notebook is essential for keeping track of your findings so far, and jotting down controlled examples of code. I personally find that a digital notebook is the best for software work. You can Copy and Paste code directly in and out of it, move it easily between computers, and carry it with you without it being heavy, no matter how big it gets. For this project I have been using Jupyter Notebook, which I can run from one of my servers inside my private intranet. For reverse engineering Jupyter's code execution features are not helpful, and the ability to add diagrams, and pictures would be useful. Jupyter is designed for scientific computing, this kind of work is a little out of it's comfort zone, but it works well enough.

It takes more dedication to keep taking notes as you switch from reverse engineering to building new code, but it pays off later when you're trying to debug the mess you've built. The thing about building from reverse engineered examples is that when you start you probably won't understand exactly how the thing you are building works. In my case this was particularly true of the collision algorithms used all over Zenphoton and now by Rustic-Zen, and I have tests that still fail due to an error in the algorithm I copied. I spent the best part of a week trying to debug this, and several pages from my paper notebook helped me reason about the geometry, and confirm the mistake was not in my implementation.

Building Big and Unwieldy Things:

This project was my first foray into working with a new development mindset: Tests! I have used tests on mature projects before, particularly at work. But I have always had trouble using them in my personal projects. As someone who does a lot of low level work, either with micro controllers or low level interfaces in PC's I have always felt like I needed to mock half the bloody earth (or at least the computer and its attached peripherals) to write a reasonable unit test.

This project being a simulation, of sorts, has a lot of self contained components, and no dependencies on external peripherals making it a good candidate for practising designing tests. From this experience I learnt that in a young project your tests grow with your code base. Ultimately there is rarely a ground truth you can base your test off that is more meaningful than 1 + 1 = 2, so as your program evolves you will need to extend and refine your tests so they always ensure your best reasoned version of "correct" behaviour.

Going into this project I held the view that tests alone aren't all that helpful when building from the ground up. I come out of my month's development with this view intact. The best bug finding tool in this program was a PNG output. Being able to see a graphical output of what your program is doing, at least in my experience, allows you to quickly identify any disparity between what the computer is doing and what you expected. This being an image generation framework, the visual output is a required part of the functionality. But even with other types of programs a visual output can be a strong debugging aid. There are a lot of data visualisation tools out there today, so getting a visual output may only require the investment of outputting your trace data to a CSV.

When building REALLY big things statistical analysis becomes mandatory. You can't hand sift through 1 million entries of your ray results. Thankfully my program is not quite big enough to warrant this approach. I got as far as outputting the 18MiB CSV file, but didn't actually analyse it.

Rust:

Rust is sold as a productivity language; it's Java for the new age if you accept a little poetic licence. I spent well over 100 hours this month working on this project. Given half of that time was spent trying to understand a monolithic C++ application that was optimised for speed not readability, I think rust did very well. The cargo tool chain was a huge time saver. Cargo is the build system bundled with the rust compiler. While technically optional it is so tightly integrated not using it would be more trouble than it has ever caused me (and that, amazingly, includes working with micro controllers). Cargo includes a testing framework, which is a massive time saver, there is also the facility to build examples independently of your library and package everything together in a well thought out and nicely integrated way. Cargo also handles dependencies sanely, making hunting for and installing libraries painless and predictable.

There is however one big point where the core of the language fell down. I actually found a language bug during development. Rust is supposed to control and limit undefined behaviour in your program, making reasoning about data flow easier, and save you from hunting null pointers. 99% of the time it does this very well. However there is a lovely bug in the conversion of floats to ints that leaves uncaught undefined behaviour from the conversion. This is fine, languages and compilers have bugs, but the lack of transparency in this issue was a little concerning. There is an issue open in the core repo on GitHub, but its been there a long time and I don't think anyone knows how to fix it elegantly.

I fell to old habits a couple of times during development, and I believe the language helped me to find a more elegant solution. How many developers can say they have never relied on a datatype to constrain a value. "Why is that value unsigned?" But with the explicit and painful nature of casts in rust I my hand was forced to find a more elegant, and ultimately more per formant and more robust solution than continuously hopping in and out of signed and unsigned types, and swapping data lengths. I really feel that using fancy data types early in development is a premature optimisation, and possibly an anti pattern. Each conversion is an opportunity to introduce a bug and create unnecessary work for the CPU. Here I think both C++ and Rust have made the same mistake; there is no 'default' integer or floating point type, selected based on the platform. So in both these languages novice programmers are forced to make decisions about the integer types they will use. There is nuance to that decision.

Summary of Lessons Learnt:

- Premature optimisation is the devil, especially data types. (Those working with serialisation are the exception.)

- Writing tests for the smallest possible blocks of code allow you to maintain forward momentum, by being able to reason that your existing code works.

- Tests are at their most valuable when you some form of data visualisation for debugging your main output.

- Keeping, updating and maintaining a notebook of your work saves you trying to juggle everything you've discovered and built so far in your head.

- Blogging about your work is a reasonably low effort way of keeping an audience and maintaining motivation.

- Forcing yourself to work on a single project for an extended period builds discipline.

I will be using all of these tweaks to my process going forward, and I guess a year from now I will see if my project completion rate goes up. With that said I will be adding a Devlogs section to this blog.

Next Steps for Rustic-Zen:

In the month I spent on this project I predict I spent about 100 hours working. In January I can't keep up this commitment, I have real life and work that I need to catch up on, so I will be parking this project again. At least I can park it with the knowledge that it works, albite with a few bugs to fix when I get some free time.

There are a few features I never got around to implementing, which I will write out as issues on the repo for future me to experiment with, but I will list them here too:

- Render Tweakables:

- PRNG Quantisation

- Prograde and Retrograde colour scalers

- 16 bit output serialisation.

- Normal Distribution in Sampler.

- Multithreading Support.

- Micro optimisations to reduce render time.

- PRNG state tracking and rollback to for animation consistency (HQZ has this, its a pain to implement).

- Shader "language" to replace the rather limited implementation that I imported from HQZ.

Finally:

I would like to thank the Level1 community for providing the motivation for this project.

I would also like to thank Micha (@scanlime) for her inspiration and support. Being able to pick her brain about the design decisions she made in the original HQZ hugely sped up the process of building Rustic-Zen.

Have a Happy New Year - SEGFAULT.