HECC CTF and Recursive Python

Written 2019-03-25 1070 words.

Last week I had the pleasure of attending my first competitive Capture The Flag event (CTF). Along with my teammates, we competed in the HECC 2019 CTF in Southampton.

Despite not placing well, we all had a lot of fun and learnt a lot in the process. The whole team is planning on attending more CTF's and training to become competitive in the future.

However I want to focus on a writing up one particular challenge. "Recursive" was a HECC challenge provided by Paloalto Networks. The challenge provides nothing more than a python file and the promise of a flag. The twist here was that that the python file was 1.5MB and obtrusificated.

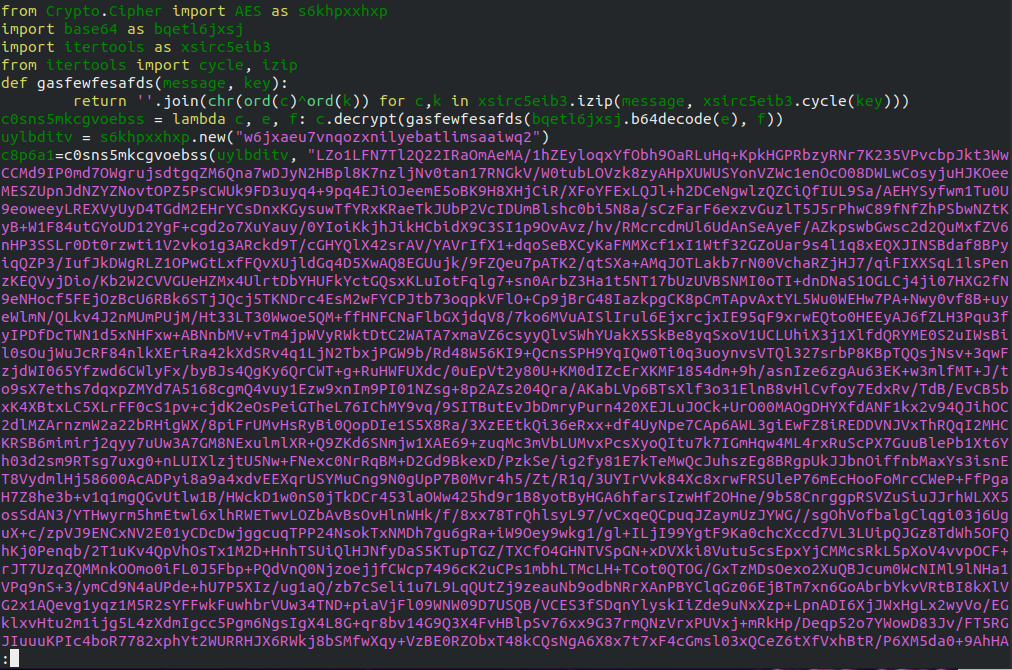

Beginning of the orginal file

Beginning of the orginal file

When I opened the file I was met with this mess. It's function was not immediately obvious, so the first logical thing to do was run it and see what I was working with.

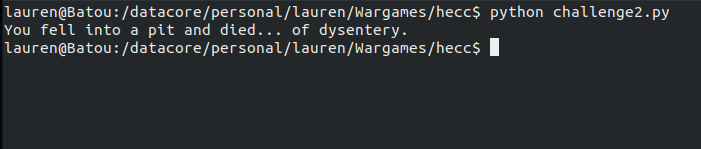

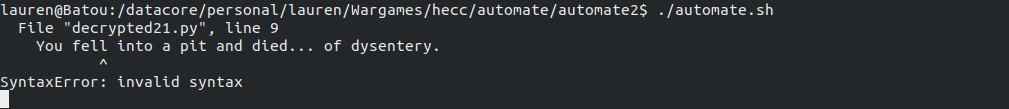

Huh...

Huh...

Nice! I liked the Oregon Trail reference, but there is a hint here and in the name "recursive". I'll come back to this later. But first lets look at that code.

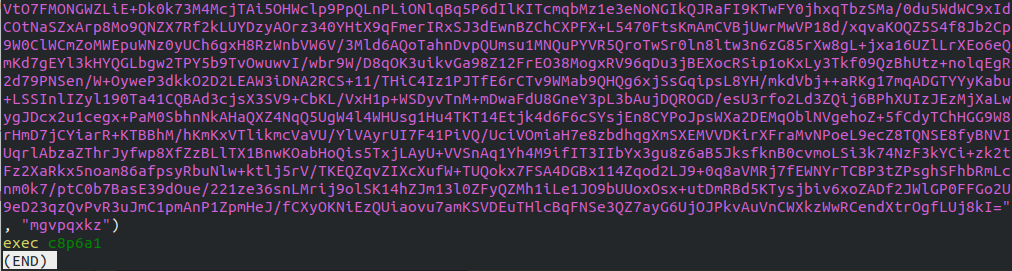

The original file, ending with an exec call

The original file, ending with an exec call

I next looked at the code in further detail. The import statement gives away that this Megabyte blob in the middle of the file is probably an AES encrypted ciphertext. But what's under that? exec... bingo.

This encrypted blob is python! Its first decrypted and then executed. But "You fell down a hole", recursively? Based on it's size and these hints I am going to guess that this block also contains a blob and execs it. Lets find out. A nice quirk of python2 (sadly lost in python3) is that exec and print have the same syntax. So swapping exec for print and running it again (piped to a file for sanity), and... eureka!

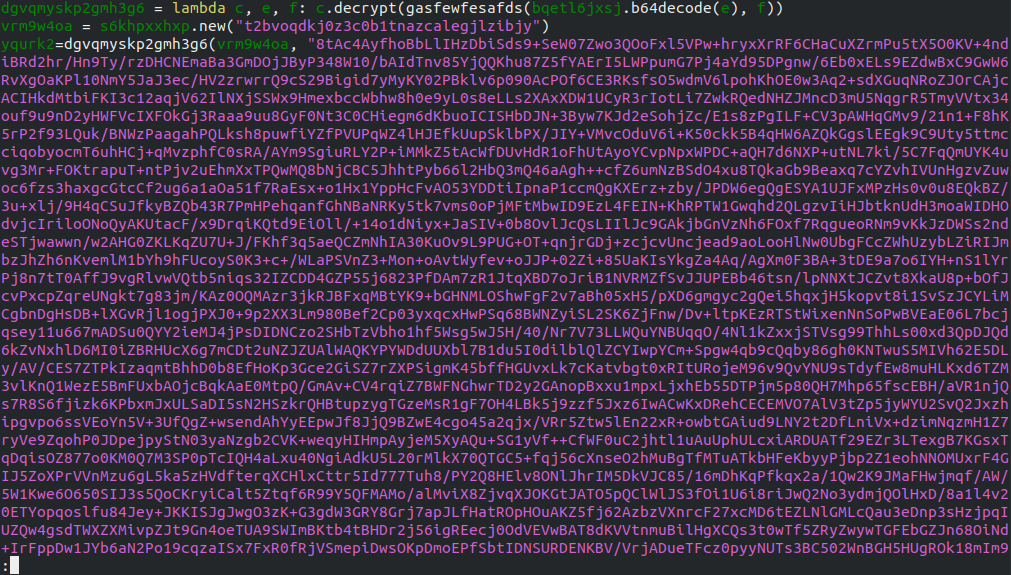

Output of printing the plaintext instead of execing it

Output of printing the plaintext instead of execing it

It is python code, and there is another encrypted block, with another exec statement.

I can just do this again, right? Swap exec for print and pipe the output to another file? Sadly its not that easy, this file won't run, its missing the declarations from before. When this block is exec'ed it gets access to all of the already defined context, but I lost that when I exported the code into a new file.

I fixed that by concatenating this new file to the original, simulating the existing context, and then replacing print and exec. This gave a third block of python with another encrypted block and another exec statement. I was satisfied it was going to be encryption all the way down.

Doing this by hand was going to take all week. The hard way to do this would be to manipulate objects in the python interpreter and try to control execution from there. But I had a better idea... Shell time!

My first shell script took the output of the previous iteration and used sed to replace all exec statements with print. It then appended the output to the python script and ran it again. Running in a loop the file grew... and grew... and grew... until it was 84MB and I decided to kill the process.

Each new iteration duplicated every existing encrypted block and then added one new one, so I was having to solve significantly more AES problems than I needed to. This was dumb, and also going to take all week!

I started analysing the fragments I had decrypted so far, looking for commonalities. Each block had the same structure, once you removed the obtrusification. It would first define a lambda function to decrypt the data it would then define a key. it would then call the lambda on a ciphertext and finally exec the plaintext.

# How the file would have looked without obtrucification:

def keyfunc(message, key):

return ''.join(chr(ord(c)^ord(k)) for c,k in itertools.izip(message, itertools.cycle(key)))

decrypt = lambda c, e, f: c.decrypt(keyfunc(base64.b64decode(e), f))

context = AES.new("k7omyjixqji4kuruu8jiukkfx1zzrnss")

plaintext=decrypt(context, "I am a ciphertext", "I am the key")

exec plaintext

# See that's not so scary!

It only depended on the imports and a defined key handling function from the outermost file. So I could define a base file containing everything before the crypto blob in the first file, still obtrusificated:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES as s6khpxxhxp

import base64 as bqetl6jxsj

import itertools as xsirc5eib3

from itertools import cycle, izip

def gasfewfesafds(message, key):

return ''.join(chr(ord(c)^ord(k)) for c,k in xsirc5eib3.izip(message, xsirc5eib3.cycle(key)))

c0sns5mkcgvoebss = lambda c, e, f: c.decrypt(gasfewfesafds(bqetl6jxsj.b64decode(e), f))

uylbditv = s6khpxxhxp.new("w6jxaeu7vnqozxnilyebatlimsaaiwq2")

Now strictly speaking the last two lines were superfulous to solving the challenge, but I didn't realise at the time.

And modified my bash script to append the output of the file to this base, still using sed to nullify the exec statements. I now controlled execution and was able to run it at a reasonable speed.

let x=0

while true; do

let "y=x"

let "x=x+1"

cat "base.py" > "decrypted$x.py"

if ! python2 "decrypted$y.py" | sed 's/exec/print/g' >> "decrypted$x.py"; then

exit

fi

done

It seemed almost insulting to solve a python challenge with 9 lines of bash.

I honestly didn't expect this to work first time. I expected to need to modify my base with more dependencies as I delved deeper into the nested plaintexts. But no such challenge arrived, and my terminal dutifully printed:

Looking Promising

Looking Promising

I had reached the bottom.

I promptly killed my bash loop and and started inspecting the output files. decrypted20 chirpily contained

if 1==2: print "Key: ---LOL I'm not publishing the flag--- "

else: print "You fell into a pit and died... of dysentery."

Charming isn't it? (there was actually the correct flag there) I'll take my 3900 points though.

I'd like to thank Paloalto Networks for providing this challenge, as well as the University of Southampton for making the event possible, and finally my teammates for putting up with my shenanigans.

See you on the trail - SEGFAULT.